From malicious narratives to semantic subterfuge

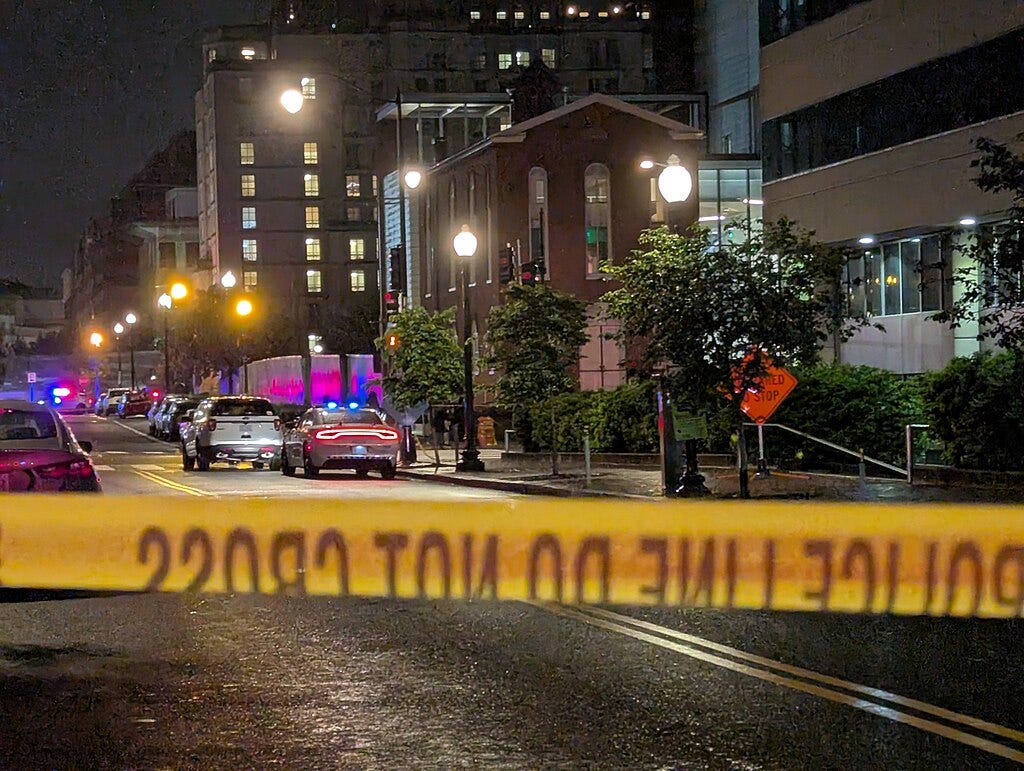

Some critical voices have rightly noted that numerous media outlets subtly imply that Israel bears partial responsibility for the horrific attack outside the Jewish Museum in Washington. Yet upon closer examination, the narratives at play reveal themselves to be anything but subtle. They verge on the overtly malicious: the suggestion that innocent lives were sacrificed as retribution for the alleged transgressions of the Israeli government. This narrative is not only morally untenable but also emblematic of a far broader, more insidious, and deeply rooted rhetorical pattern.

Indeed, a more detailed look reveals a dense lattice of insinuations, selective omissions, and suggestive interpretive frames—a rhetorical edifice that, whether born of intent or journalistic complacency, serves to blur the boundary between factual reporting and ideological persuasion. Within this discursive terrain, media figures and political actors alike often adopt a register of language that favors insinuation over clarity and emotional provocation over analytical sobriety. The terms employed are not merely imprecise; they are frequently engineered to elicit visceral reactions and to reinforce, or even intensify, entrenched adversarial stereotypes and longstanding malevolent libels. Three illustrative examples underscore the troubling dimensions of this tendency.

A war against Hamas?

Israel is not merely waging war against Hamas; it is engaged in a military conflict with Gaza as a whole. To characterize the hostilities as directed exclusively against Hamas is as reductive and misleading as it would be to claim that the Allied forces in World War II fought solely against the Nazi Party. War, by its very nature, is commonly understood as a confrontation between collective entities, not a mere aggregation of individual skirmishes between soldiers, units, or commanders. This collective lens also shapes our moral identification: pride, shame, and responsibility derive less from personal action than from the felt sense of communal affiliation. In the same way, our contemporary reckoning with the crimes of past generations is grounded not in individual culpability, but in a shared awareness of collective belonging.

This is not a claim about the moral permissibility of targeting individuals, but a recognition of the political reality that citizens—much like children with respect to their parents—inevitably share in the consequences of their leaders' choices. Moral reasoning in war differs from that in domestic self-defense. A police officer chasing a bank robber through a crowded pedestrian zone has little moral leeway to accept collateral damage; the bystanders bear no morally relevant co-identification with the robber.

A narrative that reduces the present conflict to a narrowly targeted campaign against Hamas thereby casts the remainder of Gaza's population as wholly uninvolved bystanders—comparable to pedestrians in the domestic policing scenario—thereby rendering every civilian casualty a moral outrage that appears categorically unjustifiable. Such framing not only distorts the empirical realities of warfare, but also narrows the ethical discourse in ways that obscure its complexity.

Civilians versus combatants?

A frequently invoked rhetorical trope in war reporting is the distinction, enshrined in international humanitarian law, between civilians and combatants. Yet this binary proves inadequate in the context of the Gaza war. Hamas fighters do not operate as a regular armed force; they routinely fail to meet the criteria set forth in the Geneva Conventions, such as openly bearing arms, wearing identifiable insignia, and adhering to the laws of war. Israel is thus confronted with a far more complex delineation: between civilians who, through direct participation in hostilities, may under international law be considered legitimate targets, and those who are not. This crucial nuance is often omitted from media accounts of civilian suffering or casualties, thereby skewing public perception in a way that unfairly impugns Israel.

Another important question is how much harm civilians can reasonably be expected to bear. Civilian responsibility extends beyond political allegiance or voting behavior; attitudes toward the lives of innocents—especially on the opposing side—are morally relevant. Those who endorse indiscriminate violence or show indifference to the suffering of noncombatants carry a different moral burden. Reciprocity is central here: one cannot claim rights one denies to others. A murderer cannot object to being treated as he treats others; likewise, civilians who celebrate the killing and abuse of innocents—as has been repeatedly observed in the Gaza Strip—undermine their moral claim to special protection. This affects how proportionality is judged and, to some extent, expands the moral latitude available to the Israel Defense Forces. Another nuance not only omitted from much of the media discourse but largely treated as taboo is the question of how moral responsibility is distributed among civilians in times of war.

Proportionality?

The principle of proportionality requires that anticipated civilian harm must not be excessive in relation to the expected military advantage. It is a cornerstone of international humanitarian law. Crucially, proportionality is not assessed retrospectively by tallying the scale of destruction; rather, it is evaluated from the standpoint of the military decision-maker at the time of action, based on the knowledge and situational awareness reasonably available. Legal appraisal thus hinges on intent, precautionary measures taken, and the anticipated relation between harm and military gain—not on ex post facto casualty statistics.

This distinction is frequently ignored in public discourse. Media reports, commentators, and political figures often reduce the principle of proportionality to numerical comparisons, a reductive framing that empties the principle of its normative content and casts Israel in an unjustly negative light. What may serve as a point of academic speculation in thought experiments—such as the canonical trolley dilemmas—lacks both legal and moral traction when applied to the harsh exigencies of actual warfare.

The quiet power of rhetorical drift

In the present case, journalistic treatment exhibits a diminishing concern for nuance; indeed, what emerges at times is an outright reversal of the roles of aggressor and victim—one seemingly aimed less at analytical clarity than at deflecting attention from the underlying sources of hatred and agression. At the same time, rhetorical subtleties embedded in everyday language and media narratives continue to exert influence—semantic shifts and terminological ambiguities that arise either from unthinking habit or ideological purpose.

These rhetorical mechanisms contribute to the normalization of antisemitic tropes, not by articulating them explicitly, but by rendering them familiar, palatable, and thus increasingly immune to critique. It is precisely in their apparent innocuousness that such linguistic strategies exert their greatest force—for what escapes notice is least likely to be challenged.

I think what gets missed too often is how this kind of rhetorical drift doesn’t just shift how others see Israel,it shifts how we start seeing the world, almost without realizing it.

When “proportionality” becomes a body count comparison and “civilian” is treated as an absolute shield regardless of context, it flattens real moral complexity. Worse, it slowly rewires our instincts. We begin to feel outrage at Israel by default, but almost nothing in response to celebrations of mass murder,because one set of violence is coded as “resistance” and the other as “state power.”